The Roads to Freedom: Solidarity Poland

Words by Dalene Heck / Photography by Pete Heck

I’ve been thinking a lot about the act of protest lately. Which may seem naive and trivial that here, in my 37th year of life, I am really thinking about it for the first time. I think it is fortunate that I’ve never had to. Growing up in a stable democracy, having most of my rights and freedoms go unchallenged has meant a blessed existence when compared to the majority of people across the world who have to struggle for even the most basic human rights.

A lot of this recent thought has stemmed from watching what has gone on in Turkey. How the right to peaceful protest was not only ignored by the government but met with excessive violence and slanted propaganda to sway the rest of the population. A big chunk of my heart remains in that country and has been battered as a result.

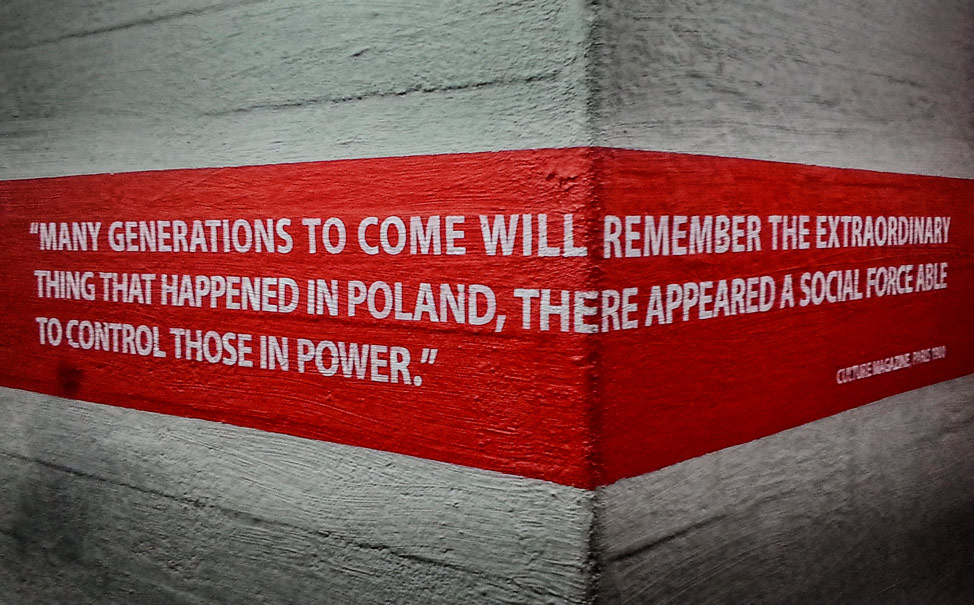

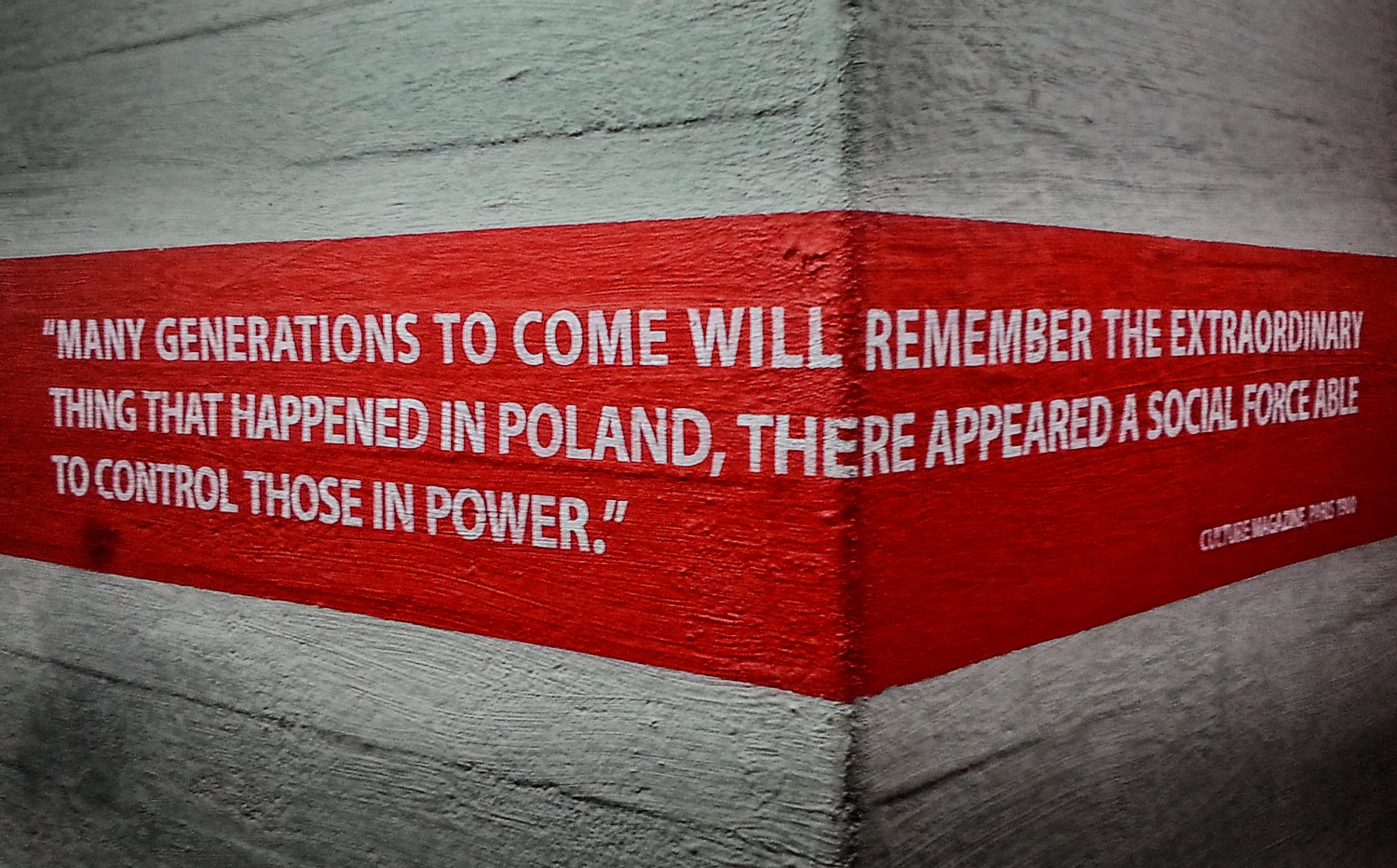

As I walked through the “Roads to Freedom” exhibit at the Solidarity Museum in Gdańsk, parallels were so obvious. Circumstances are of course vastly different, but elements of each situation are largely the same.

I may have seen, heard, or read about such things before (history repeats and repeats and repeats itself), but this exhibit hit me much harder.

The Roads to Freedom

Freedom was a long time coming, and it followed a very rocky road to get there. Poland, without doubt, has faced treacherous challenges. In this century alone, it was ravaged during WWI (although not an independent state at the time), decimated in WWII with almost 6 million lives lost, and then under the curtain of communism for 44 years. The exhibit at the Solidarity Museum begins there, in 1945, when Poland began to function as no more than a Soviet colony.

The Soviet Union convinced the Polish that they were developing a government of social justice. They used terror and propaganda to take power, prisons largely only served political goals, and food shortages were common. Grocery shopping more closely resembled hunting through crowded streets with others in the same pursuit. A significant part of the population, still recovering from the effects of WWII, at least welcomed the restoration of a somewhat normal life, and many of the harshly controlling changes went unchallenged. While some meaningful protests did exist early on, the real tides of change wouldn’t come for many years.

The Fall of Communism Started in Gdańsk

Neither Pete nor I had ever heard of Gdańsk prior to booking our trip, which made us both feel a bit ashamed upon visiting the Solidarity museum. It was here that the fall of communism started not only for Poland but for all of Europe.

Faced with harsh economic conditions and a drastic upswing in prices in late 1970, people took to the streets in Gdańsk and other northern cities. Hundreds were killed during the protests as the army opened fire on their peaceful processions. Finally, prices were lowered, and wage increases were made. Living standards shot up for a few years, but world economies soon shot down with increased oil prices and recessions in the West.

Prices rose again in 1976: butter by 33%, meat by 70%, sugar by 100%. Strikes and protests began this time nationwide. The government had no choice but to repeal the increases, making it appear utterly ineffective. Resistance to the regime grew. New opposition groups formed and were met with excessive repression once again: imprisonment, beatings, and torture.

Change Begins

Bolstered by the seemingly miraculous election of a Polish Pope in 1978, the country was inspired. During his first papal visit to his home country in 1979, Pope John Paul II did not openly encourage rebellion but expressed his hope for change. The people listened, were vitally encouraged, and the course was set. The communist leadership was faltering and again had to announce price increases. Strikes and protests began immediately, and the economy shook to a halt. In full defiance, men slept in the Lenin shipyards in Gdańsk on boxes of styrofoam, dreaming of a better life. A set of 21 postulates were written on two wooden boards which stood at the main gate – demands were clear for all the Polish people to see, but silently, so as to give the government no reason to initiate violence.

The Polish were no longer afraid. Such began the Solidarność (Solidarity) movement, and ten million people joined the newly created independent trade union.

Desperate, the government enacted martial law overnight. Based on the pretense of economic reform, the “Military Council of National Salvation” was entirely unconstitutional. The Solidarity trade union, despite its overwhelming popularity, only remained legal for 16 months. Fear and propaganda were used to try and discredit the opposition – people could be interned if there was even a whiff of not supporting the government.

Solidarity persisted. And as the communist government continued to falter through the 1980s, they began to realize that a deal with the opposition was necessary. Elections were set, and while the communists structured them such that their competitors could only run for one-third of the open seats, their political maneuvering still did not save them. Solidarity won every seat they ran for, but the new communist Prime Minister could not gain enough support to form his government and stepped down. The official opposition leader Lech Wałęsa, an electrician who led the formation of Solidarność ten years earlier, was elected in 1990 to become the leader of the Republic of Poland.

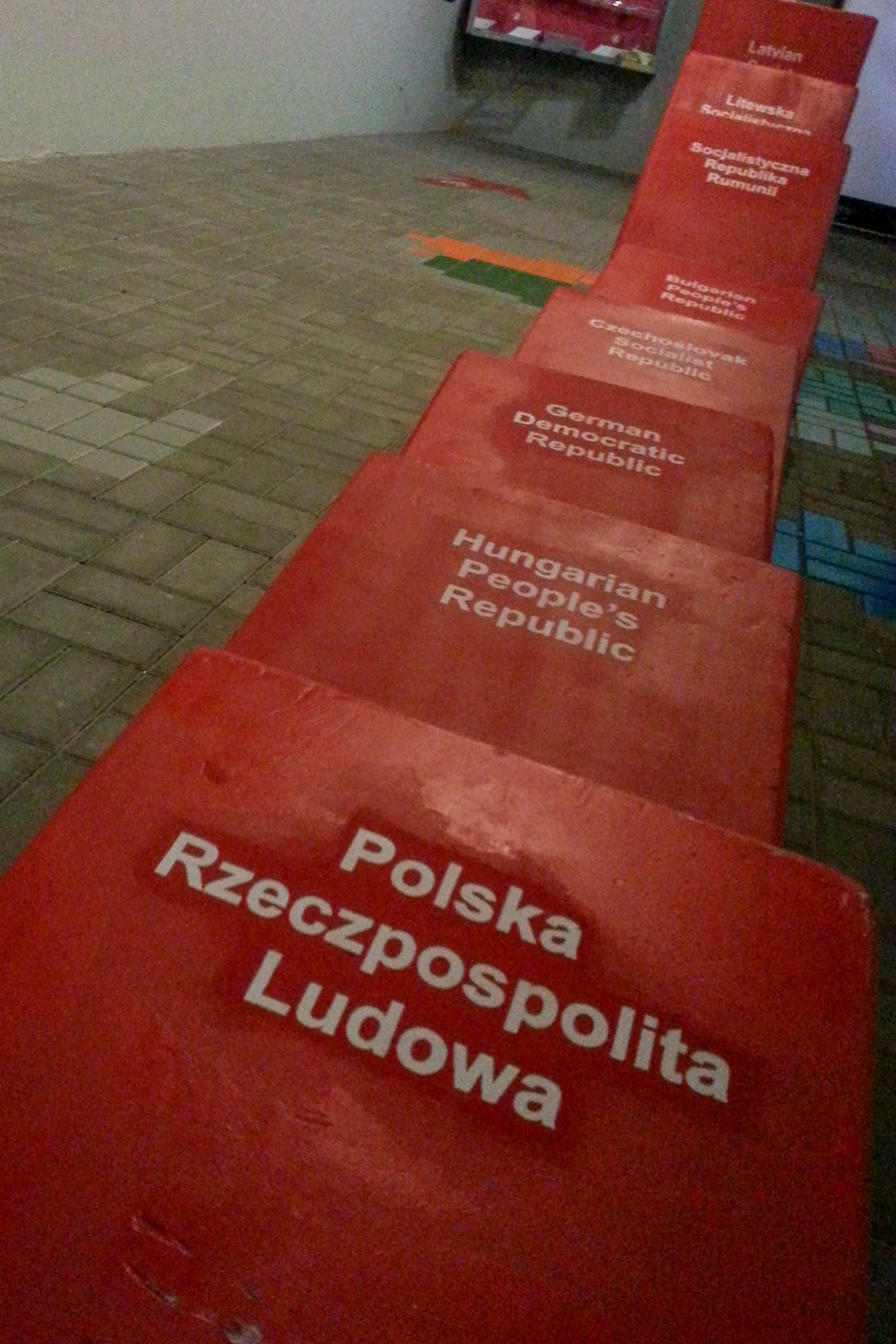

Communism was over in Poland. And it was followed thereafter by Hungary, then Germany with the fall of the Berlin Wall, and so on.

The displays throughout the exhibit are powerful. Reconstructed prison cells detailing the obscure reasons for detainment, photos of protestors numbering in thousands, a leather jacket riddled with bullet holes, secretly saved by a young man’s parents to contest the government’s claim that weapons had not been used against protestors.

Since visiting the museum, I now find myself peering into the faces of random Polish people we encounter, trying to guess their age and thus where they might have been when the fall finally came. What they remember, what their views were, how their families were affected. I want to know if they felt joy or fear when a new era was upon them. I want to know if they stood up for change.

Someone close to me once said, in a discussion about protest: “I just want to live my simple, quiet life – nothing is ever perfect.” I can understand the sentiment, but it also struck me as defiant of those that have protested important issues to secure the civil rights we enjoy today and for those that are willing to stand up to protect and further the rights of the next generation. But I suppose it is easier to accept a reduction in civil liberties in order to keep peace. That means swallowing drastic price increases dictated by a conglomerate (oil), accepting open uses of racial profiling, submitting to surveillance in the name of national security, and so on. These struggles don’t just happen over there or in the distant past. When is enough enough?

On any given day of protest, I can imagine feelings of hopelessness, not knowing where it will lead, if anywhere. I think about the people of Turkey and their strength of spirit to remain peaceful in the face of violence, the suffragettes who fought for my right to vote in Canada, the heroic showing by the masses in Egypt, and now, I deeply admire the Polish people who set the stage for democracy in eastern Europe.

I am in awe at their sacrifices of voice and life to secure their future and the years it took to establish it.

Would I have the fortitude to do it? I would like to think so. But to that extent, I hope I never have to find out.

I hope you never have to find out either! What a powerful and important museum.

It seems like a lifetime ago that I got to (stay up late!) to watch TV as the Berlin Wall came down while discussing the significance with my dad.

Memories seem to fade so easily, especially when you haven’t lived historic events. That’s why hearing about places like the Solidarity museum are so important to me. Thanks for sharing its story. And if you meet any folks who lived through the Roads to Freedom, I’d love to hear about them too.

Oh yah, and enjoy Poland! 🙂

As a product of the 80s, I remember clearly watching the events of Solidarnosc unfold in Poland, and later, events leading to the “fall” of the wall in Berlin/Germany. History seems to have had a good knack for kicking our ass, but perhaps we are hell-bent on repeating. The more I read about policies, strategies, and tactics to keep nations and people in line behind the Iron Curtain, the more I’m disturbed by the ongoing parallels to current events. People in power have paid attention, but the real question is: have the rest of us paying attention?

That is an excellent question Henry, and I think the answer is no. At least not yet…but in our lifetime, I do believe we will see some significant changes to the world as we know it (at least as North Americans).

P.S. Of note…you have proven to have an excellent memory from your childhood. 🙂

I’ve often asked myself this question – especially when I visited the church where Dr. King used to preach in Atlanta during the Civil Rights Movement. Would I have had the courage to participate in sit-ins, boycotts, and freedom rides? Would I have risked my life for the greater cause? I’d like to think that I would’ve and that I would should the need ever arise again. Awesome post!

Thanks Dana. I hope we never have to answer that question, really, but I’d be surprised if that will be the case in our lifetime. Things are messed up.

Yes it’s interesting how democracy in one country spurs events to areas closeby that see’s the impact of how the people can make changes together when they claim it and fight for a better society. Its sometimes a painful process as we see it happening today!

A thoughtful post… it is hard to imagine what it must have been like, but it is so important to try in order to try and understand a culture better.

So true Stephanie. And what is surprising me most (the more that I talk to people about it here), is how many people are wishing for the communist times back – realizing that democracy isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

“I now find myself peering into the faces of random Polish people we encounter, trying to guess their age and thus where they might have been when the fall finally came. What they remember, what their views were, how their families were affected.”

This is exactly what I think when walking down the street in China. Every time I see an older person, I wonder about the trials and hardships they faced, whether they were persecuted or if they persecuted others, what they have told their children. It’s tragic that so many people on this earth have had to experience such trauma.

I agree Heather, and it sure cements the idea that we are damn lucky for being born into the countries that we were.

It is so interesting how differently I saw Roads to Freedom. For my taste it was too polono-centric. But I always thought that it was probably a good point to start thinking about history of this part of the world. I may have been in Slavic Studies as an academic for too long. I loved your very personal take on this, and I do think that it is important to see the connections between the end of the cold war and socialist regimes – and today’s protests all over the world. If you ever make it to the Baltics, you will be able to relate your thoughts about this to the thoughts about similar museums in Vilnius and Riga – where they are yet a bit different, because those countries were actually part of the Soviet Union.

I guess I could see how it would come across as too polono-centric, for someone who has been exposed to more of this than me! 🙂 It is definitely something I would like to learn more about, and will get to the Baltics someday.

Although we were living under Communism we were not unhappy. We were certainly very sheltered in our upbringing and our environment felt safe – there were no homeless people on the streets, there were no robberies and murders. I was 8 and I remember everything and it didn’t traumatized me at all. Just politics. Thank god that my country was always protesting peacefully and we didn’t have wars unlike some of our neighbours. Now, 25 years after 1989 reality is much more brutal for people living in Eastern Europe.

Thank you for your comment Irene, and I appreciate your views.